Volcanic ash never really cooperated and caused a great deal of grief when we were trying to juggle a decision between major schedule changes and missing the scientific objectives for which we came here in the first place vs. the risk of muti-million dollar damage to the aircraft engines. Such choices are not easy to make but when you have great people on the team, it helps to come to the most educated and safe decision, and so we have. We are going to Tasmania today.

It was pouring rain in Christchurch, which wasn’t able to soak our elated spirits much. An instrument computer that would not boot was more successful at that but we were not going to give up that easily, and managed to replace it and boot the replacement in a half usable configuration to allow to limp along, collecting data. As it turned out later, finding where in the world did the replacement CPU store the data that it collected on this flight was just about as difficult as to replace it in the first place. But finally we were ready to take off, only an hour later than planned.

For the first two hours we flew low, at 16,000 feet, above the South Island of New Zealand, staying below the ash cloud warning area. The scenery was amazing, and the crew was plastered to the windows, taking pictures of the snowy mountain ranges and shimmering blue lakes below our wings. The day was clear and visibility was great but I guess nowadays you can never have 100 mile visibility with no haze: there is too much aerosol in the air, some natural but I am sure that people are adding to the mess as well. Nonetheless, the views were spectacular. From all the places I was lucky enough to visit, New Zealand stands out as probably the most beautiful country in my eyes with the most diverse scenery in closer proximity than elsewhere. There are mountains in the Rockies too, for example, but their foothills are at 6,000 feet so in effect the 14-ers are only 8,000 feet high. Here the 12,000-ers start at sea level, so they are actually 12,000 feet high and therefore look a lot more imposing. Nice humidity levels from the ocean provide for lush green vegetation, lacking in the high deserts. The only place in the U.S. I can think of that compares is probably Washington State or Oregon but I have not been there enough to judge.

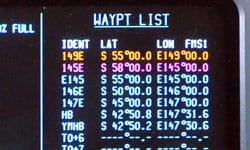

Our Gulfstream is more fuel efficient at high altitudes, so we were anxious to get up high. We were able to safely do that once we crossed 158ºE longitude. While climbing to 43,000 feet we looked over the vast clouded area underneath that started soon off the shore of New Zealand and extended as far as one could see. This is the edge of the Polar Jet, the windy periphery of the high pressure system currently located over Australia and Tasmania. Wind speeds in the jet can exceed 180 miles per hour and on occasion, these wind speeds can extend to very low altitudes, sometimes to the ocean surface. On this flight we saw only 95 knot winds (49 m/s or 109 mph) and the forecast wind speed was even lower. The cloud cover extended as far South as we flew, and was nearly continuous, with the upper cloud surface that would remind you of hard boiling milk. All you could see was the endless convective bubbles of clouds, ridges and troughs that slowly and continually changed as we flew over.

I have noticed that at a certain angle, about 100º angle of view with respect to the sun that was slightly to the left of our heading, the sun lit the cloud tops beneath us in a way that brought out sharp contrast along a narrow strip of clouds perpendicular to our direction of flight, while the rest of the cloud cover looked washed out and devoid of detail. This interesting illumination was not immediately obvious but jumped out at you if you happened to look blankly out of the window in one direction. I discovered this effect inadvertently by staring in front of myself being in a dazed state, half dreaming, half awake, trying to pay attention but too tired to concentrate. A cat nap and curiosity helped regain acuteness again and I observed this high contrast, moving, highlight of cloud tops for a long time.

At 58ºS we made our first descent. The pilots took the jet to 500 ft above the water, and the ocean was stormy. I have not seen it as threatening as this before. We flew over rough water in previous missions but in the middle latitudes of the Northern hemisphere, and the Pacific was roiling but still bluish and the clouds were puffier and lighter-looking. Here, the ominous gray cloud deck, nearly connecting to the ocean surface, was about touched by the swells, with foam caps blown off by the wind, clearly visible from our 500 foot altitude. The wind buffeted the airplane, lifting us up and dropping down, and at 500 feet it looks like you are way too close to the water to keep doing that, especially when flying at 250 knots (290 mph). It would be a fair statement though that we were much better off on the airplane that one might have been on a ship in the same area; although it is very difficult to judge the height of swells with nothing on the surface for reference, I am sure they were easily 20-30 feet high. Even though we knew we were safe, just the proximity of the unforgiving massive swells made us all uneasy. We stayed low just enough to collect the samples, and ascended higher.

It was warmer today in the cabin than usual. The Gulfstream’s air conditioners are continually pumping 35ºF air into the cabin, and to say that the rear part of it stays cool is a major understatement. People put in foot warmers while still on the ground, and I suspect part of the reason is that they want to do it while their fingers still can bend, the ability they lose in the fist hour of the flight (just kidding). You can judge for yourself from one the pictures, or believe that “this is good for the instruments”. While I certainly know that is true, I wonder sometimes how good will it be if we freeze the scientists to death for the benefit of instrument thermal balance? They looked very cold to me, and I hid in the cockpit where the pilots made the temperature quite comfortable.

We proceeded alternating between 28,000 and 500 feet altitudes four more times along the way but for the rest of these dips the seas were not nearly as rough, even though on one of the 500 foot legs we never saw the ocean, the clouds extended all the way down to the ocean surface. Only by looking at the instruments could you tell that we are that low, outside the windows it looked like you are immersed in the 1% milk, solid grayish white color with zero visibility (sorry dilute milk lovers). We landed in Hobart in late afternoon. The sun already was touching the horizon, and all we could think about was going to the hotel to take a rest.